Inside Look

WRITING THE SONG, “One Fine Day”

Kay Weaver

The melody came first. It almost always does. Sometimes I dream it. Late at night. When I’m sound asleep. But then I hear myself humming a tune. If it wakes me up, I write it down. I used to keep manuscript paper and a pen on the nightstand next to my bed. And yes, I was awakened late at night with the music for “One Fine Day” playing in my head. It was 1982.

Melody flows for me. It is spiritual. Universal. It creeps into my subconscious. It rolls through time and space nearly unphased. Words take more conscious effort. They’re earthbound. They take time. They’re harder. More demanding. Words are governed by specific languages. Locked into clearly circumscribed cultures, they are far more dependent on the times in which they are written.

I cannot point to any one influence that inspired “One Fine Day,” words and music. There was not simply a single person or one book or one painting or an event that prompted me to write the song. It cannot be merely laid at the feet of growing up steeped in classical music. Playing the majestic melodies of Bach, and Mozart and Brahms on my violin. There were countless influences. The song speaks to what I think is important. What I believe. It goes to the core of who I am. I cannot name just one, or even ten, but looking back 42 years there were a few distinct and immediate catalysts.

I had been reading again. In addition to histories, which I’ve always loved, I was devouring a range of writers and styles including: Death Comes For The Archbishop, by the Red Cloud, Nebraska writer, Willa Cather (1873 – 1947); Living My Life, the autobiography of the political activist, Emma Goldman (1869 – 1940); Jailed For Freedom, by the suffragist, Doris Stevens (1888 – 1963); and I had begun working my way through The Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson, (1830 – 1886). Not understanding some. Savoring others. I was reading the authors’ works while simultaneously searching for more information about their lives and the times in which they lived.

We have no idea what it was like to be a woman living in America in the 1800’s. It is beyond my imagining. The clothes alone would have discouraged me! We can read about it. Even write about it, but we lack the palpable experiences, the visceral reactions to the limitations, the prejudices and restrictions that governed everyday life. Unless a woman was helping out as unpaid labor in her family’s mercantile, her place was in the home. There were very few opportunities for women in the workplace. And most African American women lived and labored as slaves until 1865.

Colleges didn’t begin admitting women until Oberlin opened its doors to 15 women and 29 men in 1833. The few 19th Century women who did attend college had almost no choices for paid employment afterwards. A woman could be a nanny to small children, a teacher to young kids, and, of course, a nurse; women could take care of the sick and the dying. But to enter the professional sphere. To study law with an eye to someday being appointed a Judge on the Supreme Court, or to earn a Ph.D. and run a large company or be head of a bank – this was as far away as the moon. As a matter of fact, it was farther. When we landed on the moon in 1969, there was still not a single woman CEO of any Fortune 500 company. And no woman had ever been appointed to the Supreme Court.

For ambitious women, for women with eager minds, the opportunities and outlets in the 19th Century were extremely limited. But there was one realm where a creative woman could find freedom. And Emily Dickinson found it. She found it and exploited it and reveled in it. If a woman had pen and paper and that “room of one’s own” that Virginia Woolf so eloquently speaks of years later, if she had that and time. And given the demands of family life a woman’s selfish endeavors might have to be relegated to late at night with a single candle burning, but if she had pen and paper and time and the desire in her heart like Emily Dickinson, she could write, and no one could stop her.

My own writing had hit a snag. I had pen and paper and plenty of time. The chorus to “One Fine Day” was written along with a first draft of the first verse, an homage to Emily. I knew the second verse would honor Willa Cather and the third, Emma Goldman. The music was finished, but language was not forthcoming. It was not for lack of pen or paper or time or desire, I just couldn’t find the words.

It was nearly Christmas. With the lyrics to my song sketchy at best, I retreated to my artistic sanctuary, Paris. I found a cheap flight. I know all the cheap hotels. And I escaped to that resplendent city of light where the arts are on prodigious display and artists are revered. It was in Paris just a few weeks later that a surprise encounter inspired me beyond words.

Paris is cold over the Holidays, and rain comes at you sideways. But I love it. Walking. Thinking. Ducking into a bistro to get out of a frigid wind sweeping off the Seine. Sipping a café noir. Scribbling in a notebook. I know from my journals that it was this very sojourn in Paris when I first noticed it. Paintings by women artists were beginning to show up in the great museums of western art. The Musée D’Orsay. The Louvre. And the Musée Nationale d’Art Moderne – a.k.a. The Pompidou.

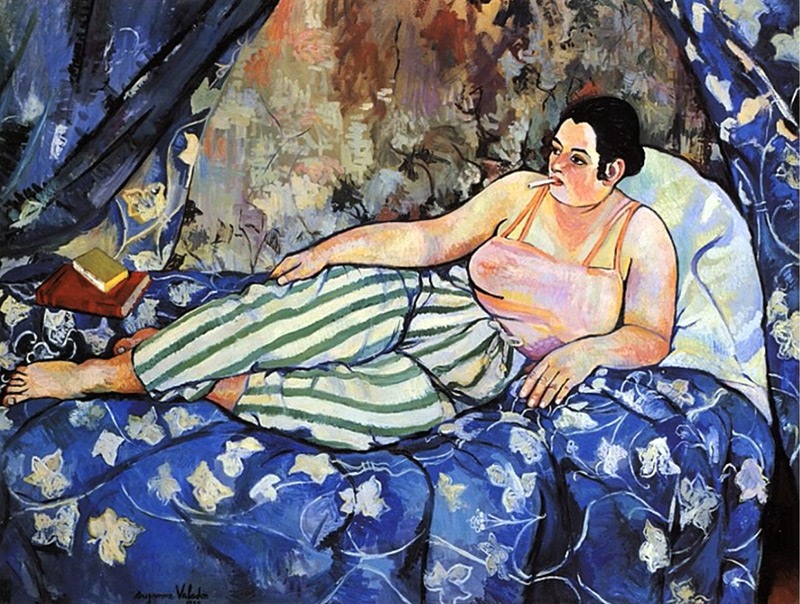

It was on one of those cold, drizzly Paris days that I spotted her. Even from across the room I knew immediately. Without a doubt. She had been painted by a woman. And as I approached her it became blatantly obvious. This was no painting of yet another naked Venus with idealized features – one more reclining nude woman rendered by a male hand and resigned to the male gaze. No passive pose here. This woman I recognized. She was defiant. Modern. Comfortable in her own skin and with her own thoughts. Lounging on her own flowery blue bed in her pj’s and confidently smoking a cigarette, she was looking off to my left and couldn’t care less who was looking at her. The painting was La Chambre Bleue. The artist, Suzanne Valadon (1865 – 1938).

I looked for information on Valadon’s life. Read about her. She was born an impoverished, illegitimate child of a laundress in Montmartre. Forced to drop out of school to help her mother earn a living, the eleven-year-old sold vegetables in the street. At twelve she was waiting tables in busy cafes while enviously eyeing artists as they set up their easels on sidewalks and in the square. Since the age of nine Suzanne wanted to draw. To paint. She wanted to learn. But access to the all-male École des Beaux-Arts was denied to her. And a tutor cost money. Valadon was determined. So, she modeled.

She befriended and posed for some of the great painters of the day. Renoir. Toulouse-Lautrec. Degas. Reclining on a chaise, nearly naked, positioning her head in the direction dictated by the painter and trying her best to look passive, Valadon asked them questions about their work. They were only too happy to discuss their art. Their technique. Show her how they got this rich color or that three-dimensional effect. She listened, and she used the money she earned to put a roof over not just her head, but those of her mother and her young illegitimate son, Maurice Utrillo. She bought paint and canvas. She bought time, and she painted. In her own, Modernist style, Suzanne Valadon painted. No one could stop her.

I left the Pompidou. Walked quickly past paintings by Dali, Matisse, Braque and Picasso. Artists whose works I know and love to study, but not on that day. On that day I wanted to keep La Chambre Bleue foremost in my mind’s eye. Once outside I headed straight to Les Deux Magots and grabbed a little round table in the glass enclosure facing L’Église Saint-Germain-des-Prés, the 12th Century Romanesque Cathedral with its 10th Century bell tower. I ordered a café noir and took out my notebook. Scribbling. Rewriting. Polishing every word until I was satisfied. Until the lyric for “One Fine Day” filled the page. Until it was finished.

I hadn’t noticed the time. I had been writing and rewriting for hours. The gray afternoon drizzle had surrendered to a stormy night. Rivulets of rain water ran down the outside of the glass enclosure channeling the red and green and bright white lights of passing cars and trending shops into streams of vivid color. My café noir was long gone, but the servers hadn’t bothered me. They saw I was busy. I caught the attention of one of them and ordered une coupe de champagne. It was the first week of January, 1983.

I closed my notebook and raised my glass to all those 19th and early 20th century women writers and artists and political activists. To the suffragists who marched and picketed and went to prison. Some went on hunger strikes and were force fed, but no one could stop them. They secured the franchise for me. I was in their debt. To all the women who came before and made my road a little easier, I toasted them all. Some by name. “To Suzanne Valadon and her Chambre Bleue, to Willa Cather and Emma Goldman. To Alice Paul. And to Emily. Oh yes, here’s to Emily.” I opened my notebook again and reread the lyric one more time. Just to make sure. Yes. Finally. It was finished.

ONE FINE DAY

Words and Music: © Kay Weaver, 1983

VERSE 1

She sits at her desk on a cold night in New England

The candle burns low as she writes her poetry

Lives lived alone, full of ache, full of passion

Sing me a song of Emily

CHORUS

And my road is a little easier cause she was here

I see a little clearer through the darkness called fear

Sister take my hand, it’s with you I make my stand

And we’ll be all we can, ONE FINE DAY

VERSE 2

Daughter of Nebraska, lover of women

Painting with words the music she hears

Her letters are burning but her life is not forgotten

Willa Cather, Red Cloud Pioneer

CHORUS

And my road is a little easier cause she was here

I see a little clearer through the darkness called fear

Sister take my hand it’s with you I make my stand

And we’ll be all we can, ONE FINE DAY

VERSE 3

Preaching the word, doing time for freedom

Tearing down the altars to hate and bigotry

The earth is her country, Humankind her people

Emma Goldman, sing your song for me

CHORUS

And my road is a little easier cause she was here

I see a little clearer through the darkness called fear

Sister take my hand it’s with you I make my stand

And we’ll be all we can, ONE FINE DAY

FINAL CHORUS

And my road is a little easier cause they were here

I see a little clearer through the darkness called fear

Sister take my hand it’s with you I make my stand

And we’ll be all we can, ONE FINE DAY